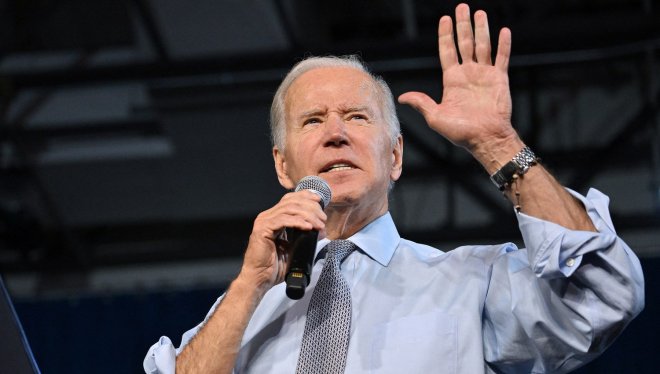

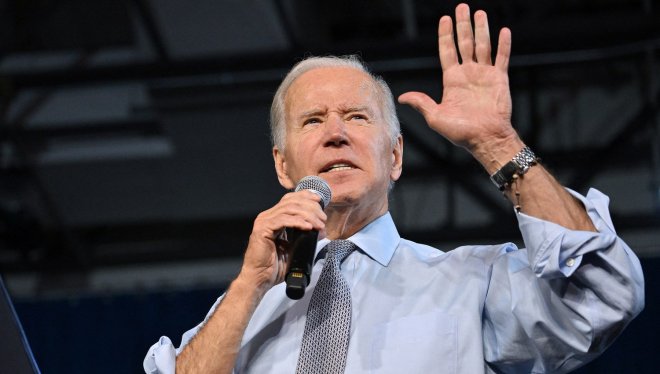

A seven-day overseas trip looks likely to prove the biggest test of U.S. President Joe Biden’s foreign policy chops since he entered office last year, with four back-to-back summits culminating in what could be his first face-to-face meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping as president.

Biden departs Thursday for Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, for the 27th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, or COP27 meeting. He then attends the annual Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN, and East Asia summits, which are this year in Phnom Penh, and the G-20 leaders meeting in Bali, Indonesia.

While the COP27 meeting will provide the president with a platform to promote his vision of fighting climate change, his administration’s capacity to make substantive pledges is expected to be restrained by the reality of shared power in Congress in the wake of Tuesday’s midterms.

More significant will be the summits in Southeast Asia starting Saturday.

Biden’s first task will be convincing ASEAN leaders in Phnom Penh that Washington remains a helpful counterbalance as Beijing seeks to assume the role of regional hegemon. (Chinese Premier Li Keqiang arrived in Phnom Penh on Tuesday, and leaves the same day as Biden.)

“Biden is going to Phnom Penh to demonstrate U.S. respect for and engagement with ASEAN, ASEAN-centrality and the role of ASEAN multilateral institutions in the security of the Indo-Pacific Region,” Carl Thayer, emeritus professor at the Australian Defense Force Academy in Canberra, told Radio Free Asia, adding that China would be in focus.

“He will also try to assuage those ASEAN leaders who are swayed by China’s rhetoric that the U.S. is the root cause of regional instability,” he said. “Biden will repeat longstanding U.S. policy that the United States will cooperate with China where it can, but resist China where it must.”

During the summit in Phnom Penh, U.S.-ASEAN relations are expected to be upgraded to the status of a “comprehensive strategic partnership” – as China-ASEAN relations were during last year’s summit in Brunei – before Cambodia hands over the group’s rotating chairmanship to Indonesia.

The future of suspended ASEAN member Myanmar is also expected to feature heavily during the summits, with human rights groups calling for the summit to enact embargoes on arms and jet fuel to Naypyidaw.

Face-to-face with Xi?

After a second day in Phnom Penh, Biden heads off to Bali late on Sunday for the all-important 17th G-20 leaders conference.

After months of speculation about whether Russian President Vladimir Putin would attend, Indonesian President Joko Widodo said on Tuesday that it was likely – though not certain – his Russian counterpart would not be at the event in person but may instead attend some sessions virtually.

That has meant the biggest question is whether Biden and Xi will meet privately at the G-20, with the pair having not met since Biden took office.

A face-to-face meeting between President Joe Biden and China"s President Xi Jinping could take place at the G-20 meeting in Indonesia. (AFP file)National Security Council spokesman John Kirby told Voice of America on Friday that there were not yet any plans for Biden to meet with Xi, who was just re-elected to a third five-year term as China’s leader.

A face-to-face meeting between President Joe Biden and China"s President Xi Jinping could take place at the G-20 meeting in Indonesia. (AFP file)National Security Council spokesman John Kirby told Voice of America on Friday that there were not yet any plans for Biden to meet with Xi, who was just re-elected to a third five-year term as China’s leader.

“There are working-level discussions right now about the potential for a bilateral meeting, but I don"t have anything to report at this time,” Kirby said, adding only that Biden looked forward to “an opportunity to engage with foreign leaders about so many shared challenges” at the G-20.

Any meeting between Biden and Xi would be expected to focus on Beijing’s support for Moscow amid its ongoing invasion of Ukraine, new U.S. export controls on the sale of microchip technology to China and American concerns about Beijing’s alleged plans to invade Taiwan.

Each has caused growing tensions between the United States and China over a period in which international diplomacy has been increasingly relegated to virtual meetings – first by the pandemic and then by Beijing’s extensive preparations for last month’s Communist Party congress.

“There is value to in-person meetings that no number of virtual meetings or phone calls can replace,” said Peter K. Lee, a security expert and research fellow in the foreign policy and defense program at the United States Studies Centre in Sydney. “The pandemic has limited the kind of leader-led diplomacy that is an important element of statecraft.”

Lee said a face-to-face meeting between Biden and Xi would be an important opportunity “to take stock of the current trajectory of U.S.-China relations” since the pair last met virtually for two hours on July 28.

“There are so many disputes at the moment such as over Ukraine, Taiwan, North Korea, and technology decoupling where the two leaders are at an impasse but nonetheless need to be talking,” he said.

Breathing room

In contrast to the ASEAN summit in Phnom Penh, where Biden will be looking to offset growing Chinese influence in the region, a face-to-face meeting on the sidelines of the G-20 may provide a chance to put a floor on increasingly tense relations between the world’s two major powers.

Any such meeting would importantly take place with major domestic political events in the rear-view mirror in both countries, giving both sides some breathing room to broach compromise and cooperation.

“After the midterms and the 20th Party Congress, neither leader will be under pressure from domestic politics to appear hawkish toward the other,” said Nathaniel Sher, a senior research analyst and expert on China-U.S. ties at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

“There are too many troubling issues both domestically in China and the U.S. as well as internationally — economic headwinds, climate change, the threat of nuclear war — for either leader to welcome a further deterioration in the bilateral relationship,” he said.

The very fact of any one-on-one meeting could be positive, Sher added, for the broader perception it could create about U.S.-China cooperation.

“Diplomatic engagement at the top sends a message to the bureaucracies in both countries that they can re-engage at the working level,” he said. “Reopening dialogue channels is particularly important after the flare-up in tensions over Taiwan last summer.”

That result of a possible Biden-Xi meeting might be more important than the specific outcome of anything they discuss, according to Thomas Fingar, a fellow at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and the former chief U.S. intelligence analyst.

“The meeting would not solve specific problems, but the fact of the meeting would demonstrate that Biden (and the U.S.) is willing to work with Xi/China when and where it is possible to do so (e.g., on Ukraine, nuclear security, climate issues),” Fingar said in an email.

“It would also make it possible for lower-level Chinese officials to re-engage with their American counterparts,” he said. “That might not happen, but it can’t happen unless sanctioned by Xi.”

Detente unlikely

But even then, the prospects for a detente seem dim.

Ja Ian Chong, a professor of international relations and expert in Chinese foreign policy at the National University of Singapore, said while Biden and Xi might have an interest in their countries easing ties, the room for maneuver would be limited by the widening chasm in their interests.

“Both sides have incentives to prevent some uncontrolled and uncontrollable downward spiral in relations,” Chong said, but “both sides are likely to signal resolve to each other” on any disagreement.

“Beijing’s insistence on a more forceful style for pursuing its interests, Washington’s determination to resist such moves,” as well as deepening mutual suspicions developing back in Washington and Beijing, he added, “likely make anything more than very small steps very difficult.”