Meryem Ismayil was a law student at Xinjiang University when she took her life five years ago.

The 22-year-old Uyghur from Aqerik village in Xinjiang’s Shayar County was distraught over the detention of her father, a Chinese Communist party cadre and member of the village’s People’s Congress.

Chinese authorities sentenced to nine years behind bars in 2017 for “threatening national security.”

Meryem and her father, Ismayil Mijit, are among the hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs listed in police records that are part of a larger cache of documents and records known as the Xinjiang Police Files.

The files, published in May 2022, were obtained by a third party from confidential internal police networks. They provide inside information on Beijing’s internment of up to 2 million Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples in northwestern China’s Xinjiang region.

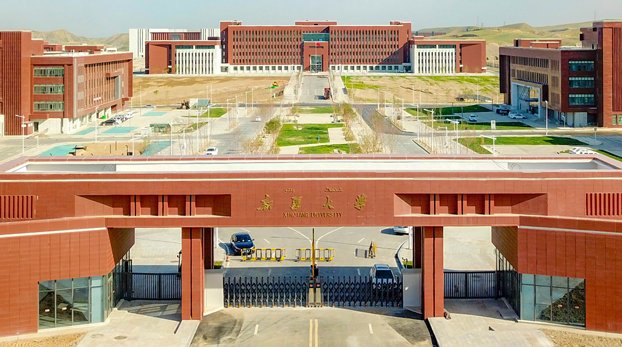

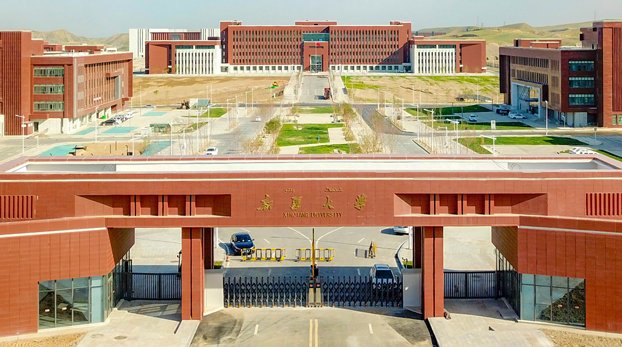

Meryem Ismayil, who began her law studies in 2013, hung herself in her student dormitory at the university in Urumqi on Dec. 19, 2017.

The police files indicate that her father’s arrest earlier that year and continuous police interrogation of her distressed mother, a retired village secretary, were the factors that caused her to commit suicide. The files also say that her father died in prison.

In 2017, Chinese authorities intensified their crackdown on Uyghurs and other Muslim Turkic minorities in Xinjiang and began detaining them in prisons or “re-education camps.”

While they targeted Uyghur intellectuals, prominent business people and Muslim clerics in a wider effort to erase Uyghur culture, they also arrested ordinary people for alleged illegal religious activities and other infractions deemed contrary to national security and regional stability.

According to the file, two police officers, Wang Wei and Ömerjan Mamut from Xinjiang University, recorded information about Meryem and forwarded it to relevant authorities.

Fresh information

A Radio Free Asia inquiry into the deaths of Meryem and her father yielded fresh information about the tragedy.

A Xinjiang University police officer confirmed that Meryem died five years ago, but that the incident was a sensitive case that he could not discuss. Another police officer said it wasn’t possible to provide a comprehensive account of Meryem and her family in a short time.

RFA also contacted police officer Ömerjan Mamut who had been assigned to monitor the vicinity of Meryem’s dormitory. He had reported that apart from her death, police did not observe any abnormal situations at Xinjiang University during that time.

But Mamut declined to answer RFA’s questions and noted a specific directive prohibiting the disclosure of such information.

“I can’t discuss it,” he said. “We are prohibited from talking about it on the phone if anyone calls to ask about it.

Another police officer contacted by RFA who wanted to remain anonymous because he isn’t authorized to speak to the media, said Meryem had used her father’s mobile phone during the vacation and watched what was deemed “illegal information” on the device.

As a result, authorities interrogated her father, who took responsibility for the incident to protect his daughter, the officer said.

Consequently, authorities charged him with “threatening national security” and sentenced him to nine years in prison, he said.

A police officer from the Gulbagh township police station in Shayar county said Meryem’s father died in prison in June 2022. He had been arrested for “watching illegal content,” the policeman said.

“He passed away in prison due to an illness,” he added, saying that the body was turned over to the family.

The police officer said he was responsible for overseeing five critical individuals, including Meryem’s mother, and could summon them at any time to come to his office. He also monitored the comings and goings of people close to them.

“We’d pay attention to their conversations with others and their daily activities,” he said. “They needed to get a pass from the office if they wanted to leave the village.”

Translated by RFA Uyghur. Edited by Roseanne Gerin and Malcolm Foster.